Alexander Djikia. Katharevusa

-

Date(s)

30 May — 03 June 2007

-

Address

Stella Art Foundation

Helexpo, Athens, Greece

About the Project

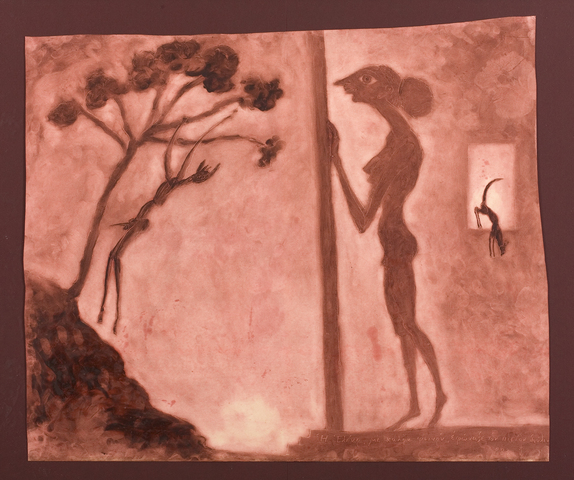

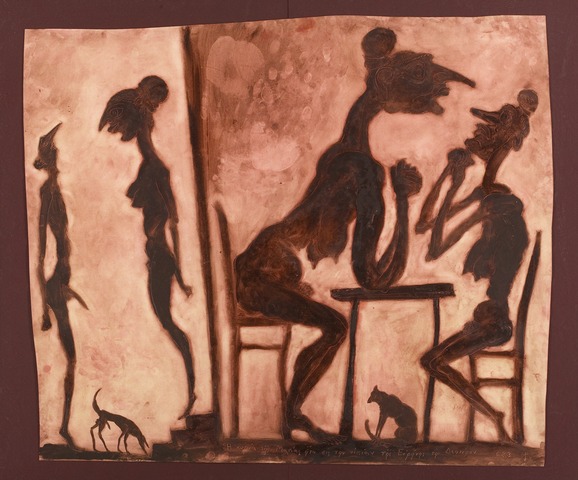

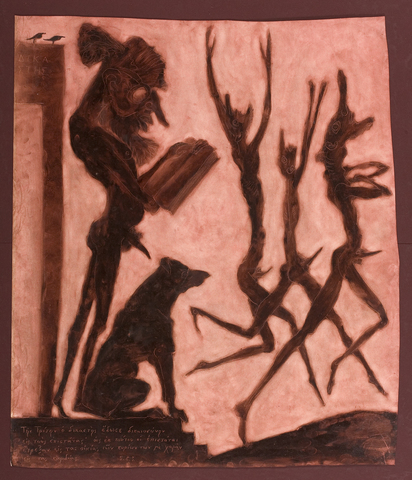

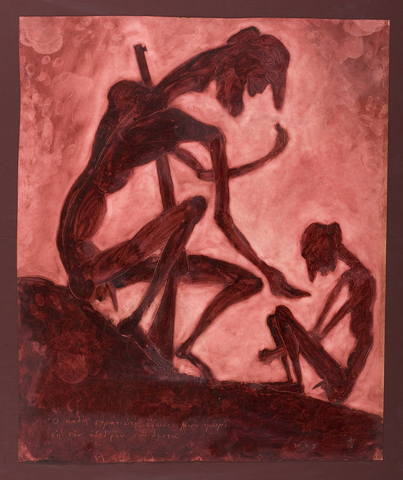

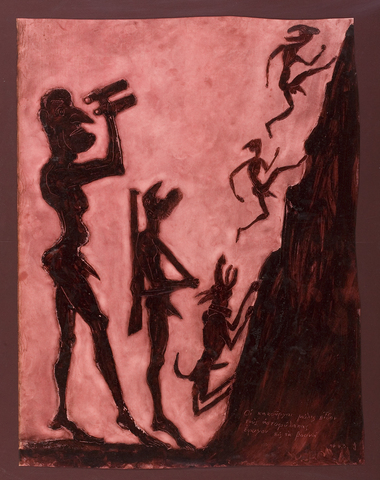

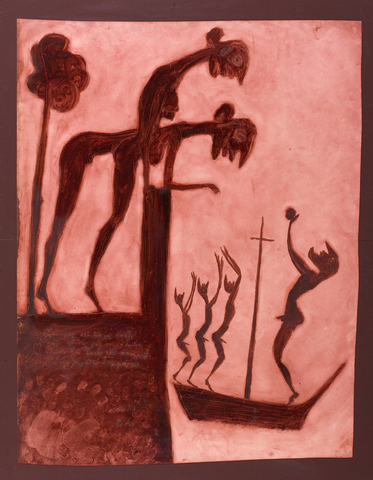

Alexander Djikia’s works always bind imagery to a text, and this is how they arrive at a strikingly original synthesis between literature and visual art. Having been trained as an architect, the artist turns each of his works into a carefully thought out project combining intellectual calculation with brilliant improvisation. Djikia’s themes are exceptionally diverse — from dreams to grotesque domestic scenes to subjects derived from ancient Greek art.

Katharevousa, the large series of graphics being presented by the Stella Art Foundation in its Art Athina 2007 programme, belongs to the latter set of Djikia’s themes. However, its ancient Greek ancestry is not so straightforward. At one point the artist began learning Greek with the aid of a textbook written by the priest Sophocles Andriades and published in Great Britain. The grammatical examples (in Greek) from that primer became the inscriptions on each sheet in the series. The images themselves are in the style of ancient Greek vase paintings from the pre-classical era. Their stylization, however, is quite tentative. The artist does regularly show figures in silhouette and in profile, while separate features of the body (such as the noses, chins, breasts and phalluses) protrude from them with a completely archaic expressiveness. Nevertheless, there is no suggestion here of the geometric or of the ancient “order”, and all the subjects (which are also grammar book examples) are handled with psychological accuracy.

The artist’s admiring yet free-wheeling attitude toward the source of his inspirations applies as much to the underlying technique as to the content. To begin with, he applies a thick layer of dull red pigment to paper with uneven edges. Like a sculptor or vase painter, he then removes or clears away the background to arrive at the forms he needs and finally incises it with the minimum details, including the Greek text. His works become profoundly organic through this fusion of visual and technical components. One could even say that Djikia’s art exists like organic matter: it produces all the forms and meanings that existed within it from the beginning — already in the idea and in the core of the image.

Vladimir Levashov