Walrus Ivory Tower

Alexey Tarkhanov, Kommersant / 20 May 2009

The Viennese Kunsthistorisches Museum, the former Emperor’s museum famous for its classical collections, has inaugurated an exhibition of Moscow conceptualists Elena Elagina and Igor Makarevich under the title “In Situ.” The event was organized by Stella Art Foundation and sponsored by Mercury Group and Dorotheum Auction House. Curator of the exhibition Boris Manner placed works of Makarevich and Yelagina next to paintings by Snyders, Brueghel, Rembrandt and van Dyck. The match was appreciated by Alexey Tarkhanov.

Viennese Kunsthistorisches is an imperial museum, like Louvre or Hermitage. The institution boasts the world’s best collection of Brueghel’s works, including his “Babel Tower,” one of the most accomplished and mysterious paintings of the artist. “I was always thrilled by this tower,” says Igor Makarevich. “It reminded me of the fact that Elena and me were born at the time of a great utopia, although we only found it at the stage of its complete degradation. We were small bricks of an incomprehensible building.” The artists grew a huge fly agaric mushroom right at the center of the Brueghel Hall. The mighty mushroom supports a column cap of classical order with the Tatlin’s Tower on top. This Babel tower of the 3rd Communist International growing out of mushroom vapors is as naive as a sculpture from a children’s playground, as a walrus ivory souvenir overbloated with humidity.

Brueghel’s tower speaks volumes about the futility of human ambitions. The great construction project is in full swing: pulleys are creaking, carpenters are raising the roof beams high, the summit of the tower is disappearing in clouds. And yet, the foundation of the tower is already breaking down and no effort of the king, in front of whom stonecutters prostrate themselves at the foreground, will change the end result: the tower will never be completed, just like Stalin’s Palace of Soviets never did. One can see it this way. There may be another view, though — one could see the tower as a hymn to human endeavor, always inadequate and futile in historical perspective, and yet requiring the same day-to-day courage as washing the dishes.

This jump above one’s head, this exerting oneself and the nature beyond limits, is what the entire art of Elena Elagina and Igor Makarevich is about, and in the context of an art history museum all their works — such as the torture bed for slowing down the breathing built by инженер accountant Borisov, who dreamt of becoming a tree, which is set in front of a painting by van Dyck depicting Santa Rosalia at the holy table of Our Lady, with the skull exquisitely drawn by Van Dyck at the foreground “rhyming” with the wooden skull of Buratino exhibited under glass in the next hall, or Elagina’s story about the alchemical science of Stalin’s Academician Olga Lepeshinskaya accompanied by laboratory notebooks and implements displayed in showcases resembling tools of torture or sugar tongs — act as witnesses of genuine unhappy, but heroic biographies.

Visiting the exhibition promises many surprises for the Viennese. Even if they don’t notice the Mushroom Tower, driven by a desire to go straight to Brueghel’s paintings, their attention will be arrested in the next hall, at the wall with two Snyders’ Fish Markets. They will discover here a typical middle Russia landscape with a hole in the middle and a clyster pipe inserted in it, a wooden carving board in form of a fish with a rubber gut and a tin flounder cut out of a plaque with an inscription “Stop! Exclusion Zone!” These are all items from the Closed Fish Exhibition displayed by Makarevich and Yelagina in 1990. They were reconstructing the exhibition items guided by titles from a Soviet catalog published in 1935, while the “fish cut-outs” looked like cut canvases in Lucio Fontana’s style. In this environment, Snyders, with his fish tables resembling foodstore advertising posters, appears as a strikingly Soviet artist, a minstrel of socialist affluence. It is at this point that the viewers begin to understand that something unusual is going on in the museum and that they are about to encounter some unfamiliar people and stories in familiar halls.

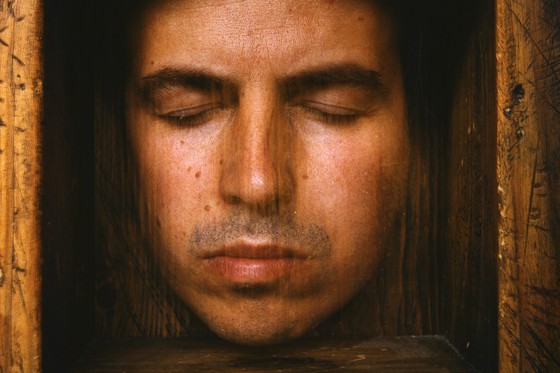

They are also about to meet Igor Makarevich himself: his project “Alterations” dating back to 1978 is presented in a side gallery. These galleries were intended by the architects of the Emperor’s museum to house small-format paintings, mainly portraits, which were too small for the space of the central halls, and these galleries are also overflowing with masterpieces. Among them, the stages of the “Alterations” series — photographs stylized as Dürer’s portraits — are inserted: the face of the artist is being gradually covered with bandages. First the mouth, then the eyes, then all the face, eventually revealing a posthumous plaster mask. It is the first and the last “personal” work at the exhibition, and it was this work that was chosen by the curators for the In Situ poster that one encounters at all the road junctions of Vienna. In all the other works the authors just peep out from behind the back of their characters: here Makarevich poses in a mask of Buratino, there Yelagina tries on Lepeshinskaya’s glasses. It all culminates in a composition on the theme of Rembrandt’s “Ganymede.” This new eagle carrying away Buratino, who is peeing with fear, painted in sweeping strokes and placed in the fold of the Rembrandt Hall, is so funny and moving, that the viewer, stopping with a gasp, will say: “Well, this one seems to be more lively!”

“We didn’t want to hold an exhibition in a separate hall,” Sabine Haag, Director of the Kunsthistorisches Museum, explains. “We wanted to integrate contemporary artists into the museum’s setting.” That’s a good point: it is in the context of a great museum that it becomes clear that Elena Elagina and, especially, Igor Makarevich are very serious classical artists, successors of the crude, yet efficient Soviet artistic tradition that was turning people into bricks and forcing painters to produce “fish cutouts,” hoping that they will grow into new Rembrandts. I am very happy for these artists, who, although very respected, renowned and widely cited, are, in my opinion, still undervalued. This exhibition project is a reward for everything they did in their life, for the fact that, while participating in all sorts of collective actions, they nevertheless didn’t let themselves to be distracted with trifles. If you have to become a brick in some structure, then let this structure be a real Babel Tower!