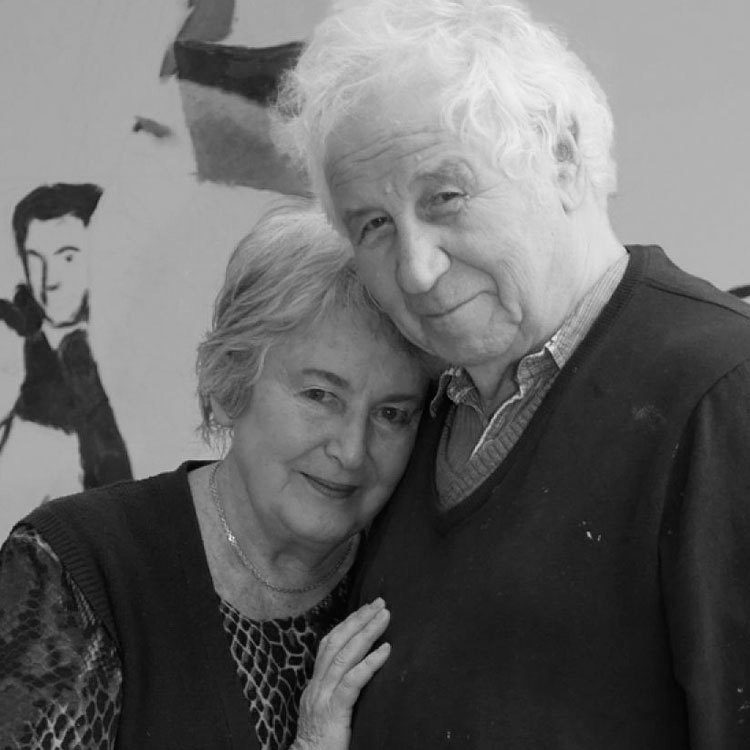

Ilya and Emilia Kabakov. Saint François d’Assise

-

Date(s)

01 December — 04 December 2008

-

Address

Stella Art Foundation

House of Moscow in Yerevan, Armenia

About the Project

Curator:Anastasia Dokuchaeva

Ilya Kabakov (born in 1933) is the ironic intellectual artist, and a major star of the Moscow conceptualism; Olivier Messiaen (1908-1992) — a French composer made famous by his light-bringing music and theoretic investigations. In a courageous attempt to bring these two artistic conceptions together in a single work, Ilya and Emilia Kabakov undertook the decoration of one of Messiaen’s central pieces — the opera “Saint François d’Assise”, which was later staged as part of the Ruhr Triennale in Bochum in 2003. This show became known as an example of an extraordinarily happy symbiosis of music and the stage decorations, as well as revealing an unusual facet of the artist’s talent.

Ilya Kabakov is not only the most internationally recognized contemporary artist in Russia. His very name is evocative of the ironically passéist rethinking of the Soviet reality, which was largely responsible for his initial popularity. The distant coldness of the researcher, together with the material wretchedness of the object of this research, the notorious “kommunalkas”, Kabakov-style, did not always allow one to see and to get a feeling for the timeless notions — the “melancholic question without an answer”, as the artist himself put it — that ceaselessly emerged behind these external constructs.

This master’s choice to decorate an opera inspired by Roman-Catholic dogmatic tradition was a challenge both for Kabakov and for Messiaen. As a result, however, a new and very impressive work of art came to be. The visual and sound elements were mutually enriched and amplified, and all the more artistically powerful for it. This resulted in theatrically ideal proportions, whereby the image created by the artist is subordinate to the music and to the dramatic qualities of the work, so that the scenic “decorations” becomes just as philosophic as they are ornamental, and yet the effect is achieved without any dissonance or rivalry with the music. Arguably, it is his early experience in book illustration, followed by the creation of an entire host of characters, each with a detailed and thought-out history, that allowed Kabakov to demonstrate in theatre also his virtuosity and the rare gift of reshaping words and even the abstract sound of the music itself as visual imagery.

The opera itself is dedicated to the latest period of the life of St Francis, it lasts five hours and in the course of its eight scenes the audience witnesses what is a gradual contemplative initiation in the mystery of faith rather than any kind of dramatic plot development. The author of the libretto is Messiaen himself, and this is worth noting, especially its being his first attempt in opera, which he had been hesitant to undertake for many years. He probably would have never embarked on the project if it was not for the remonstrance of Rolf Liebermann, the Director of the Paris Opera, and a personal request by François Mitterand, the French President. Messiaen had always felt close to the Church and to Catholic spirituality, and he had already created, in the course of his life, a number of spiritually themed pieces. Further, from 1931 and until his death he served as the organist of the Holy Trinity church in Paris. Despite his close adherence to the Catholic tradition in his work on “Saint François d’Assise”, the opera did not become a sermon or a religious exhortation in musical form. It is closer to an exalted aesthetic and spiritual experience or an ecumenical contemplation full of symbols, sometimes vague and uncertain.

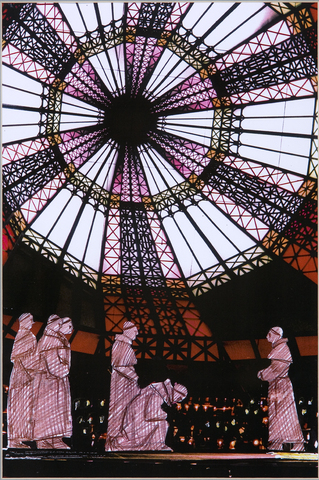

Scenes from St Francis’ life and his personality itself were fairly popular in pictorial art from the 13th century onwards. During the past three centuries, as the mainstream of the artistic tradition moved over to secular and worldly subjects, this imagery gradually disappeared from the masters’ works. Thus, the staging of “Saint François d’Assise” can be interpreted as a meeting point where the old tradition that goes back all the way to Giotto’s frescoes (this is coyly reflected in the way the scenes are presented as friezes in an almost two-dimensional ‘fresco-like‘ space) interacts with conceptualism, externally laconic yet saturated on a semantic and contextual level.

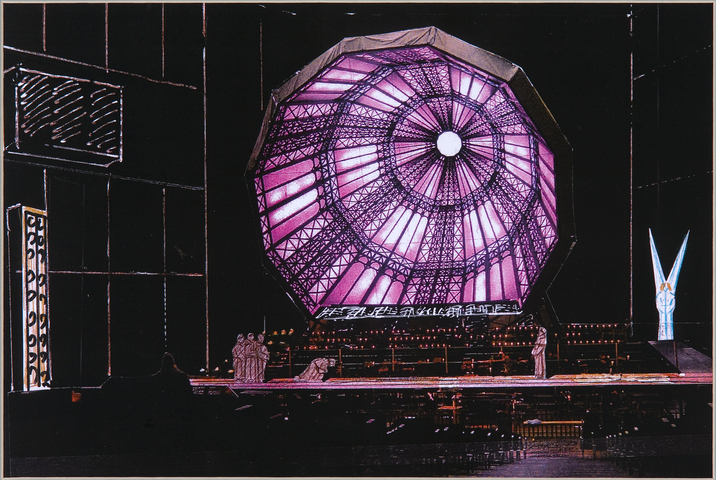

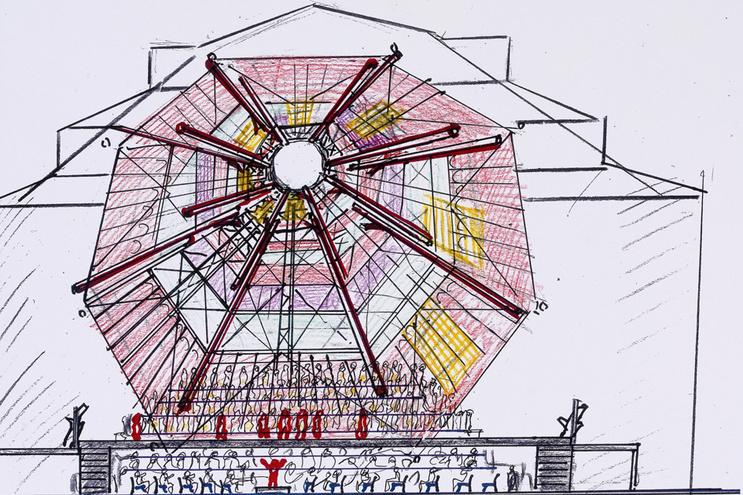

The scenography of this opera is, in its own way, a development — albeit in a somewhat unusual direction — of Kabakov’s famous notion of “total installation” that would absorb the audience fully, enveloping it with its semantic and material space. According to the artist, pictorial art has now passed the baton to installation in the Eastern European tradition he is part of, giving the audience direct access into the picture. The space of the stage, on the other hand, cannot help returning us to the central concept of the Renaissance that determined the course of art up until the 20th century. Then, the structure of the depicted space was perceived in comparison to the perspective as we see it looking out of a window frame. At the same time, theatre allows to amplify, further and further, the effect of profound physical an emotional involvement of the audience in the artistic event as it unfolds before and all around it, and this is highly desirable and valuable for Kabakov as a master of the art of installation.

The initial entanglement of conflicting artistic tendencies resolves itself as a brilliant and harmonious theatrical solution. Namely, an enormous dome was erected in the middle of the stage, inclined in such a way that its vault seems to cover not only the actors but the spectators as well. The clear and simple outlines of the frame are reminiscent both of the famous dome above the Florence cathedral by Filippo Brunelleschi, and of gothic window crosses, or the grid-like constructions in modernist architecture. This simultaneity, bringing together several different epochs, resonates in a wonderful way with the timelessness essential to Messiaen’s music. There, cacophonic sounds inspired by the natural world combine with surprising ease with the innocent delicacy of classical tunes.

The semantic significance of the dome as one of the earliest symbols for the sky, eternity and even God turned out to be scenographically important also from the point of view of the simultaneous symbolic union for the audience of the music’s numerous semantic layers. In one of the most elevated meanings of these words, the “world” onstage and in front of the stage and the “temple” behind the stage are interconnected and mutually defining, which definitely corresponds with the mystical and enlightened image of the founder of the Franciscan order — St Francis — it is enough to recall the famous “sermon to the birds” episode of his Life. This scene, in fact, takes up forty-five minutes of the opera.

The opera is an outstanding artistic event in every sense of the word. It is very rarely performed due to its musical complexity, both technical and semantic. This work of Olivier Eugene Prosper Charles Messiaen is in many ways a culmination of his extremely diverse musical interests and his sophisticated theoretical constructs: intricate rhythms that are often based on non-European musical heritage, dramatic harmonies, his own theory of the modes of limited transposition, as well as his perception of sound as colour and his research on the singing of birds. “Saint François d’Assise” is a spiritual work not by virtue of the composer’s choice to concentrate on a well-known religious motif, but rather due to Messiaen’s approach to his own music as structured mysticism. In the words of the prominent music critic John Freeman: “The luminous “Saint François d’Assise” is manna for mystics, birdwatchers, chant enthusiasts and devout Catholics”. With Kabakov’s decorations, this opera is now also manna for any modern art lover.

Anastasia Dokuchaeva