Boris Orlov and Sergei Shekhovtsov. Parsunas non grata

-

Dates

05 October 2023 — 18 February 2024

-

Address

Stella Art Foundation

-

Hours

12 p.m. — 9 p.m., Wed. — Sun.

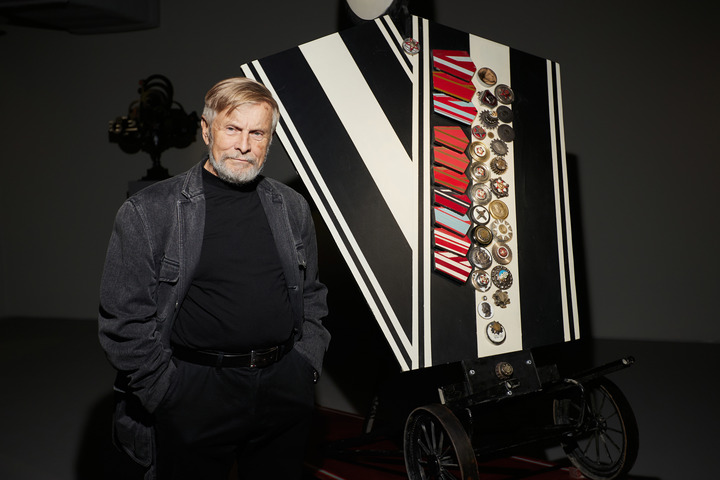

Stella Art Foundation presents the first large-scale exhibition project in the Foundation’s new premises: “Parsunas non grata” by Boris Orlov and Sergei Shekhovtsov. The exhibition will bring together more than 60 art pieces, including first-exhibited works by one of Sots art founders Boris Orlov, and the sculptures by Sergei Shekhovtsov that cover the artist’s 25-year oeuvre.

Both authors are bound by a long-term friendship. Their works are also related by addressing themes of the excluded, repressed and hidden. The title, “Parsunas non grata”, refers wittily to one of the exhibition’s key projects [1] as well as points to figures (persons) of silence, displaced into the area of the collective unconscious.

Boris Orlov, who stood at the origins of Sots art, has been developing a strict system of the Soviet ideology’s subconscious functioning since the mid-70s. When discovering the plastic signs of great styles in the socialist realism’s official visual language, Orlov becomes a pathfinder or a psychoanalyst, who follows these tiny “lapsus linguae” to the invisible base of the Soviet myth, repressed from the official language.

The artist’s words in this connection: “I was most interested in the phenomenon of empire, and some time ago nobody could even utter this word out loud. Being so young and brave, I began to develop this theme in my works. Studying the entire experience and operating principle of the Soviet propaganda machine gave me the entire visual experience of the Soviet Union, of its base on the visual heritage of all world empires: from Alexander the Great through Rome, Napoleon, the Stalinist style and straight to Brezhnev. The theme of power has always been very important to me, but I have never been involved in politics myself, I cannot be called a political artist, it is wrong. I am rather a researcher, observer, artist-political scientist.” [2]

At some point, Boris Orlov is a realism artist who “only” records and describes the system of the indecent underside of ideology’s mechanisms functioning.

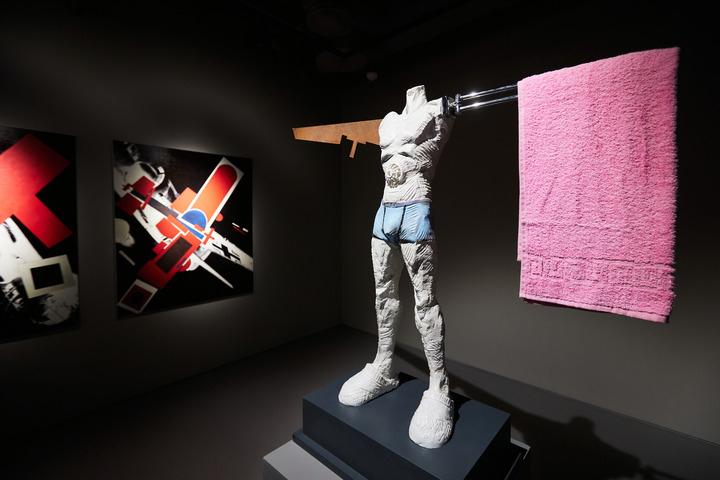

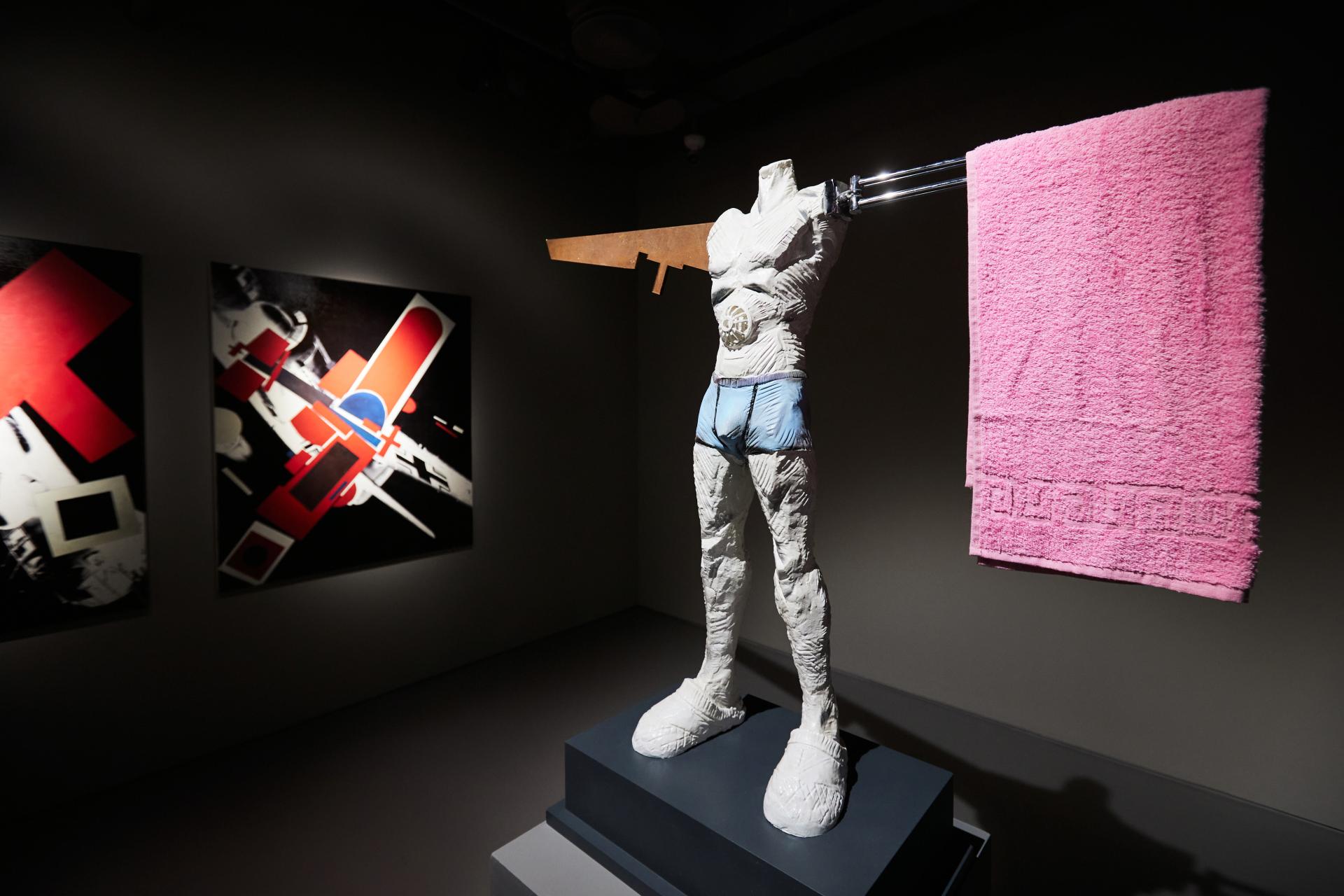

We also have a slightly different view on an excluded object in Sergei Shekhovtsov works, who addresses discarded and rejected shabby images of mass culture and everyday life. Made from “ignoble” industrial materials, often covered with chaotic graffiti, Shekhovtsov’s deceptively light sculptura secunda seems unfinished.

Here is what the artist says about his works: “In 2001, a feeling of the world as a soft, amorphous, deceptive matter just emerged. And the first project I wanted to do was about the illusional world around me. In general, it was a pop art statement, so the material processing with a graffiti tool enhanced the feeling of illusion. The texture, the story of softness and hardness, it was all important..." [3]

The works’ objects are in a state of constant formation and, by avoiding final form, keep moving. In conditions of endless mutating and merging, the objects and characters of Shekhovtsov’s works cannot divide a space between them and become expelled into the endless emptiness of the signifier, trembling in front of the spectator with a curved plastic side.

No wonder that the artist’s favorite characters were the excluded and the city residents, deprived of civil rights, the homo sacer of the urban fauna: pigeons and stray dogs.

[1] “Parsunas” series by Boris Orlov (1976 - 2018)

[2] Interview: Elena Verkhovskaya for Interview Russia

[3] Interview: Faina Balakhovskaya for the catalog of the exhibition "The Short Montage"

The text by Boris Manner, senior curator of Stella Art Foundation, which he dedicated to the project:

"The very title of the exhibition, "Parsunas non grata," contains both the description of its subject and its interpretation. The Latin expression persona non grata, coming from the language of diplomacy, means a person enjoying immunity who cannot be prosecuted by the judicial authorities of the host country, but can be expelled from its territory. "Parsuna" (the corruption of the Latin "persona"), on the other hand, brings together Roman and Russian contexts. "Parsunas" were early portraits of Russian tsars and high officials painted in the 17th century and based to a considerable degree on the icon-painting traditions. Thus, references to the Roman and Russian empires are fused in one word, bringing to mind empire per se, one of the central themes of Boris Orlov's work.

An empire is a totalitarian political formation inherently aspiring to be an absolute value, with any social phenomenon being perceived as its particular feature. Boris Orlov, one of the most prominent figures of sots-art from as early as the 1970s, counters this political totality with the totality of his aesthetic approach. Employing, among other things, some techniques of pop art glorifying and sublimating mass culture artifacts, the artist has managed to "secularize" specific artistic and political pictorial symbols of the Soviet era and provide them with an aesthetic form.

Boris Orlov insists he is not a political artist. This is certainly true, because he gives the matter of politics an aesthetic language, making it into an object of his art without proclaiming any programmes or belief systems. Here, the viewers find themselves on a shaky ground, as he uses ambiguous notions and dubious references. The spectator is not at all sure about what is actually meant by the artist. His works are imbued with a very particular sense of humour and virtuosity of artistic performance, giving the viewer true intellectual and sensual satisfaction.

Sergei Shekhovtsov, Orlov's friend of many years, employs a somewhat similar strategy in his own work. His sculptural pieces do not address politics in the context of empire. Yet, just as with Orlov, his main preoccupation is the notion of totality, though it is interpreted in more phenomenological terms, as a totality of the material world around. This world of his consists of everyday objects, which brings his art closer to pop art. The artist's hand turns his subject matter into something fully devoid of any form. Shekhovtsov transforms trivial household items into some surreal entities: a radio set, for example, takes on features of a human face (or, maybe, it is a human face turning into a radio). This way he achieves the multiplicity of meanings similar to the one we observe in Orlov's works. The nominal object dissolves, and the privilege of giving names to new forms is delegated to the viewer. The viewer is puzzled at first, but soon this puzzlement releases itself in a liberating laughter."