Anastasia Khoroshilova. Exercises

-

Dates

11 December 2008 — 18 January 2009

-

Address

Stella Art Foundation

Skaryatinsky pereulok, 7

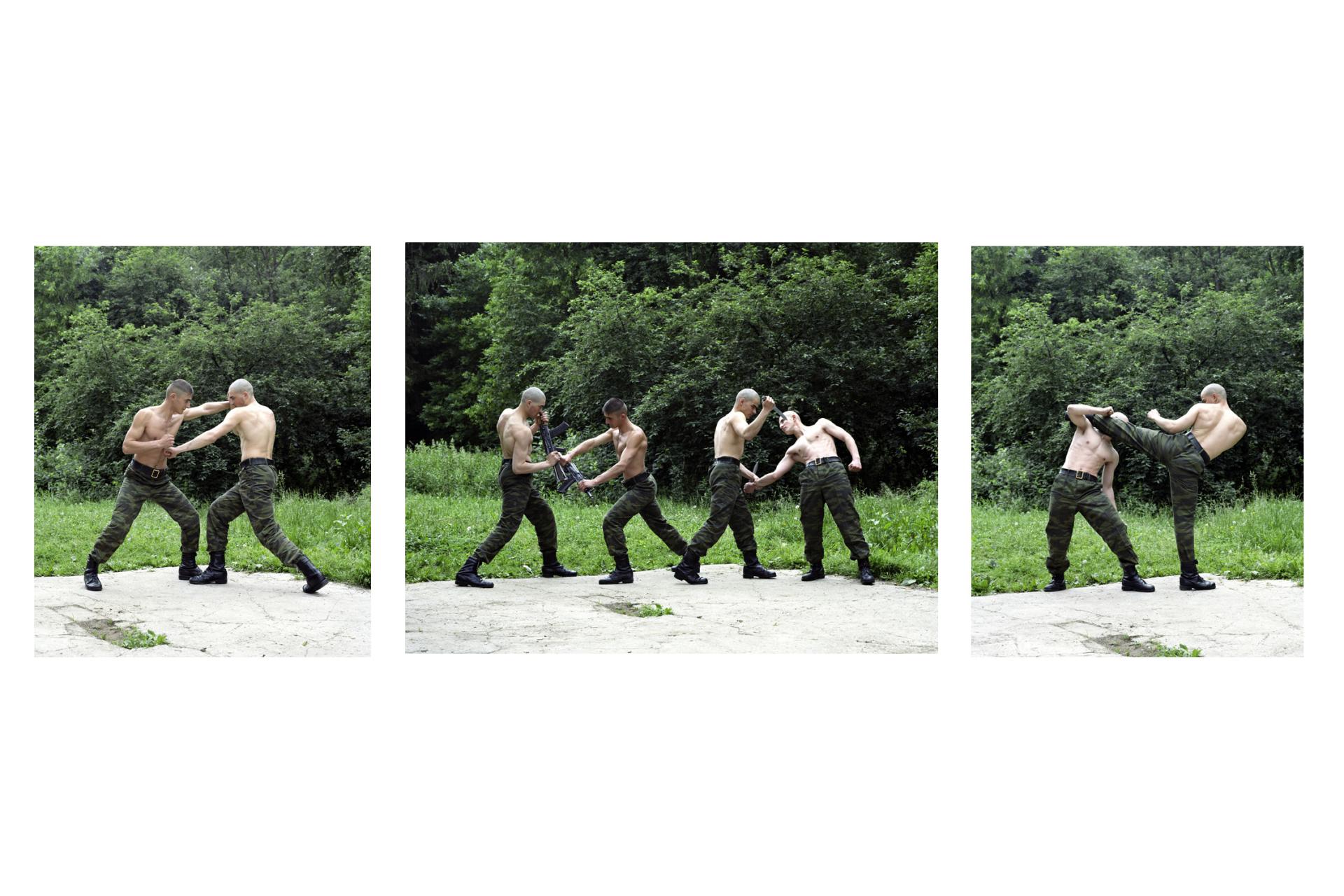

Anastasia Khoroshilova based her new project on her own photographic pictures of Russian soldiers demonstrating hand-to-hand combat techniques. There are five separate images and two large triptychs. Objective filming style, natural light and colour, a tactfully unassuming title. The project is free both from pacifistically critical and neo-imperial overtones. It has its own pathos, to be sure, but of a different kind.

According to Ms. Khoroshilova, the initial impulse for this work came from her impressions of Greek vase painting, with its habitual representations of fighting between gods and heroes. The same culture is responsible for the notion of pathos (from Greek, meaning “suffering”) that Aristotle develops in great detail as part of his aesthetic system. Suffering (due to death, or other tragic events) becomes the result of the protagonist’s own actions, caused by his passions, and is meant to evoke empathy and fear in the audience, eventually resolved in their cathartic experience. Given that the aesthetic “formulae” of the Antiquity thread the entire European history and culture, it comes as no surprise that their vague images are also visible in any representation of violence in contemporary media. It is a different issue that the emotional intensity of modern photographic and video images is almost undone by their sheer quantity in our life. Moreover, war today has ceased to be a symbol of high tragedy and turned into another word for crude violence, while pathos has evolved into something characteristic of arrogant and narcissistic behaviour that, far from bringing about catharsis, evokes a sense of shame in a sensitive spectator. The problem is, however, that the elimination of pathos in contemporary visual art is hardly an unambiguous achievement. Irony, which came in its stead, has indeed freed art from a throng of false intonations, but it has also deprived it of a major energy resource, and undermined its emotional contact with its audience.

In “Exercises” we find an attempt to return to the normal state of things. Photographic realism is combined here with the double fictionality of the object. What we are witnessing is a staging of a fighting boot camp, but its aim is, in the end, a very real elimination of the enemy. In other words, the “passionate” actions of the characters are void of self-sufficient theatricality, and are full of brutal pragmatism, so that future tragedy is discernible in the routine “army performance”. The dialectics inherent in the art “made from life” correspond especially well to Khoroshilova’s ethics and the technology of her work. The openly staged shooting process fixes the phases of the action aligned so as to fit the purposes of the shooting, and the staging itself renders the process of polishing close combat techniques very clearly. The latter are as close as possible to a real conflict situation, just as a technologically up-to-date photographic simulation may be close to the “documentary truth” of the real-life material.

If we were dealing with shooting of a “still life”, there would be nothing special about such a combination of pre-staged simulation and documentary faithful representation. In this case, however, we have an example of directly staged photography. This is quite unusual in Russian artistic tradition, dominated, as a rule, either by the “casual shot” aesthetics that breaks privacy norms as a matter of principle, or the stylishness of an ostentatiously staged shot. The only pity is that antiquity-style harmony remains unattainable. And yet, modern photography is no Greek theatre, and it counts suspense, rather than catharsis, among the attributes of its eternally prolonged moment.

Vladimir Levashov