Timing Is Everything

Nicholas Cullinan, Artforum / 01 September 2011

How long is a piece of string? This is the banal question prompted by the twine trailing down the wall in the first room of the Russian pavilion at this year’s Venice Biennale. Emerging from seemingly nowhere, it beckons one to pull it—and lengths of it have already piled up on the floor, a record of previous tugs from passersby. The situation is one without any real origin or end. And it is, therefore, an apt introduction to the work of the Collective Actions group, which married futility with visceral experience in a kind of never-ending now.

By choosing Collective Action, and its founder and leader, Andrei Monastyrski, to represent Russia, curator Boris Groys faced a daunting challenge: How to make the archival documentation of the group’s remarkably elusive activities speak to the viewer, and how to render its endeavors legible without eliding their original context and enduring complexity? His solution was a multipronged curatorial strategy: On view are photographs, texts, and ephemera relating to the group’s performances; an installation including two banners, one a Cyrillic-emblazoned replica of a prop used in a 1970 performance, the other bearing an English translation; Monastyrski’s deliberately drab 1987 series “Earth Works,” featuring deadpan photo-graphs of urban sprawl and miscellaneous Soviet non-sites; and projections of Monastyrski’s recent YouTube videos, in which he continues to mine the everyday, though the aesthetics of the Communist collective have given way to those of the digital-era democratization of images. The result is a compelling chronicle. The trajectory traced by the show’s varied elements illuminates, if it does not exactly clarify, Russian collaborative and participatory artmaking in the realms of performance, photography, and video from Soviet times to the present. Oscillating constantly between embodiment and representation, objects and non-objects, the exhibition resonates in important ways with current practice within and beyond the Russian context. Above all, what this rigorous artistic and curatorial project demands is that the viewer consider not art per se, but rather the reverberating traces and memories that lie in the wake of art.

A long-overdue reassessment of the influence of Monastyrski and Collective Actions, particularly with respect to Russian performative practices of the 1990s, is currently under way. Monastyrski’s first retrospective, at the Moscow Museum of Modern Art last year, marked a watershed in that process, and so of course does the Venice show, which is particularly revelatory in its presentation of the early, collaborative work. Collective Actions, whose original members were Monastyrski, Nikita Alekseev, Georgy Kizevalter, and Nikolai Panitkov, formed in 1976 and immediately established itself as an alternative art community that had little use for static objects, focusing instead on the production of contingent events. The installation at the Russian pavilion highlights a number of actions that took place over the ensuing decades. All followed a similar plan: A small group of people (usually fifteen or twenty trusted coconspirators—secrecy being perhaps the most prized commodity under Communism) would be summoned by telephone to a site in the countryside outside Moscow. Those who showed up (over the years, the ever-changing roster of participants included some of Russia’s most prominent artists, such as Ilya Kabakov and Pavel Pepperstein) would typically be instructed to perform various tasks, blurring the distinction between participant and spectator in a way more connected to socialist notions of collective subjectivity than to, say, the winsomeness of Fluxus interactivity.

These pilgrimages in the name of art were as ascetic as they were arduous. Fleeting and modest events, sometimes bordering on the absurd, they often took place against a backdrop of snow-covered fields, which knowingly nodded to the white voids that played host to Kazimir Malevich’s Suprematist compositions of the 1910s and ’20s—as in Pictures, 1979, where pieces of colored paper were arranged in different configurations against the snow. In other, less picturesque events, Collective Actions sought to recuperate the political imperatives lurking behind Malevich’s still puzzlingly opaque late paintings, which he produced only a few years after his avant-garde triumphs. In The Third Variant, 1978, for example (represented in the Russian pavilion by a group of photographs), a grotesque and comic mannequin with a red balloon for a head evokes the phantasmagoric figures populating Malevich’s paintings of the late ’20s. Standing faceless and mute against abstracted patchworks of farmland, the figures dramatize the agonizing pressure the artist faced in those early-Stalinist years, suggesting an ambivalent desire both to conform to the strictures of socialist realism and to obliterate them—to obliterate the human form itself. In Collective Actions’ reenactment of this struggle, the dummy’s balloon head was eventually pierced by a participant, whereupon it exploded in a cloud of white dust; the remains were then laid to rest in a “grave” dug in the field. One of the paradigmatic and emblematic sites of Soviet production—the agricultural fields that were supposed to feed and propel the Socialist Utopian triumph, and on which Malevich’s bizarre abstract-figurative effigies gaze in such unmistakable, if enforcedly tacit, critique—thus become for Collective Actions once more the site of refusal and negation. By eschewing the metropolis and seeking an agrarian setting that provided a much-needed veil of secrecy, the group found a way to negotiate the paranoia of cold-war Communism while flouting the constraints that circumscribed artistic expression in the Soviet Union.

Replacing the Utopian city of the future, that beloved dream of the twentieth century’s political and artistic vanguards, with an exurban heterotopia of the present, Collective Actions made ostensibly apolitical works that were in fact profoundly polemical. In the seemingly innocuous The Slogan, 1977, for example, participants created a red banner emblazoned with an irresolute phrase from a poem by Monastyrski — I DO NOT COMPLAIN ABOUT ANYTHING AND I LIKE IT HERE, ALTHOUGH I HAVE NEVER BEEN HERE BEFORE AND KNOW NOTHING ABOUT THIS PLACE—and strung it up in a snowy field ringed by bare, scrubby trees. This apparent admission of apathy defiantly upends historical avant-garde notions of defamiliarization and revolutionary awakening by advocating the banal acceptance of one’s surroundings. For that very reason, however perversely, it becomes a kind of agitprop.

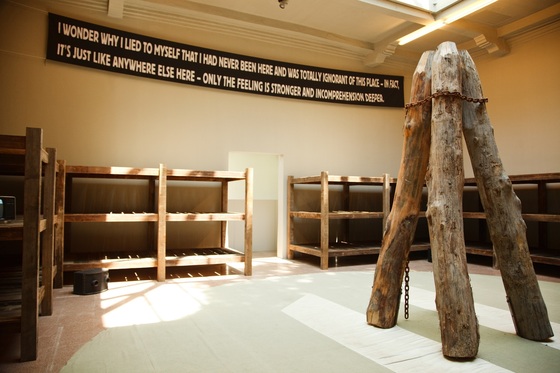

But in the pavilion, such radical disjunctures between form and content, context and meaning, are alluded to in a rather stilted fashion. Whatever the exhibition’s strengths, resuscitated remnants simply can’t translate the original function and effects of the work. The two banners that hang in the main room hark back to The Slogan’s 1978 sequel, when the group created a new banner: I WONDER WHY I LIED TO MYSELF THAT I HAD NEVER BEEN HERE AND WAS TOTALLY IGNORANT OF THIS PLACE—IN FACT, ITS JUST LIKE ANYWHERE ELSE HERE —ONLY THE FEELING IS STRONGER AND INCOMPREHENSION DEEPER. This incomprehension must surely be felt by the viewers who see such artifacts entirely divorced from their original contexts, settings, and narrative sequences. The other objects in the gallery—a wooden gondola mooring and bunks that evoke a gulag dormitory, which along with the banners and sundry additional elements constitute Monastyrski’s installation 11, 2011—feel similarly dissociated from the space and one another. Indeed, glancing first at the Russian text on one banner and then at its English counterpart, one can’t help but feel that the transposition from one language to the other emblematizes the multiple problems of translation and reenactment vexing the project as a whole. This obdurate, static restaging only serves to theatricalize and concretize a practice that always resisted these tendencies, tnan deliberately courted ineffability, and that was never intended to coalesce into anything that could deemed an “installation.”

As with any historical exhibition of this kind of work, the extensive use of documentation in Groys’s show is as problematic as it is necessary. In the case of Collective Actions, there’s an argument to be made that intensive mediation is apposite for a practice that, as Groys notes in the accompanying catalogue, always privileged contemplation over action, the group’s name notwithstanding. But this should not be understood as a privileging of passivity. Collective Actions’ model of spectatorship was engaged, open, thoughtful—contemplative. There was contemplation after the fact as well; in the wake of events, the group would study its documentation, analyzing and discussing what had occurred. Be that as it may, a curatorial enterprise that seeks to contemplate contemplation is an entirely different proposition, one no less difficult or complicated than an endeavor to reenact action, and one feels this conundrum keenly at the Russian pavilion.

Collective Actions’ emphasis on the present or, more precisely, on presentences, in opposition to the teleological Soviet thrust toward continually deferred promises of futurity, is the basis on which the group claims its position as a key protagonist not just in Russia but also internationally during the 1960s and ’70s. Groys, who as a theorist and historian has developed a nuanced critique of modernist temporality, argues in the catalogue that the relentless futurity of modernity in its Communist and capitalist permutations constitutes a kind of blindness. Collective Actions used contemplation in an effort to instantiate contemporaneity, to make the present visible and assert it as the ground of politics and of art.

“This attempt actually constituted the phenomenon that we call ’contemporary art,” Groys writes. His transnational emphasis takes the group out of the peripheral spaces (both literally and metaphorically) of the fields outside Moscow and places it in the crucible of current artistic practice. What he has not managed to do is to rekindle the crucial temporal dimension of Collective Actions; he has not brought its gestures to life in the register of the present. In a contradictory way, the show’s historiographic address—the pastness embedded in the facture of old photographs; the abandoned, disused look of the banners—affirms futurity, the absent complement of the pavilion’s tableaux of backward-looking melancholy. Had a little more thought gone into not only the theoretical imperatives driving the practice of Collective Actions but also the show’s execution—had there been more effort to determine what to do with an art of negation and reflection in a radically altered context and for a necessarily estranged audience—the Russian pavilion might have spoken to viewers in much more vivid and suggestive ways. A practice that does not entail labor, or even production in the strict sense of the term, perhaps does not lend itself to retrospective display. But artifacts must still be made to exist in the present if their meanings are to migrate and multiply with them.

Nicholas Cullinan is curator of International Modern Art at Tate Modern in London.