A Russian Guru at Work in Venice

Claudia Barbieri, The New York Times / 13 June 2011

VENICE — Was Jeff Koons turned away from the party celebrating the opening of the Venice Biennale’s Russian Pavilion?

As a small group of journalists, art critics and other invitees in the courtyard of the Palazzo Ca Foscari watched, a man who looked like Mr. Koons walked up to the gate. After a brief conversation with a security guard, he turned away and left. But it was dusk, and the gate was several meters away, making it difficult for the group inside to be sure of what, if anything, they were seeing.

Making it, in fact, a perfect example of life imitating the art of Andrei Monastyrski, the founder of the Collective Actions performance art group. His work “Empty Zones” has turned the Russian Pavilion into one of the most relevant spaces at the biennale, which runs until Nov. 27.

Stella Kesaeva, the commissioner of the pavilion, and her chosen curator, the Russian art historian Boris Groys, have turned over the entire building to Mr. Monastyrski, the guru of the Moscow Conceptualist art movement.

As a philosophical doctrine, conceptualism maintains that universal truths exist only in the mind. In the conceptual art that emerged in America and Europe in the 1960s, artists adopted that idea to create works in which the preparation and intention behind their installations and performances were part of the work, and the physical manifestation itself was almost beside the point. In the Soviet Union, conceptualism became a route for artistic expression and survival.

“I looked around and saw that many important things happened in the ’70s that had never happened before and will never happen again,” Ms. Kesaeva said. “The art reflected the life of the times.”

“I wanted,” she added, “to show what was going on behind the Iron Curtain.”

Mr. Groys said Mr. Monastyrski’s work with the Collective Actions group — creating clandestine, participatory performances, involving artists and spectators alike, outside Moscow — “was absolutely new at the time.” As an open platform for unauthorized expression, it was “officially unacceptable — and conceptualism developed outside of official recognition.”

In the pavilion’s three rooms anchored by a large central space, Mr. Monastyrski, born in 1949, has charted the history of Collective Actions — from its origins in the repressive Brezhnev-era 1970s, through the collapse of the Soviet system in the 1980s, to the present day — using photographs of its performances, archival documents and videos.

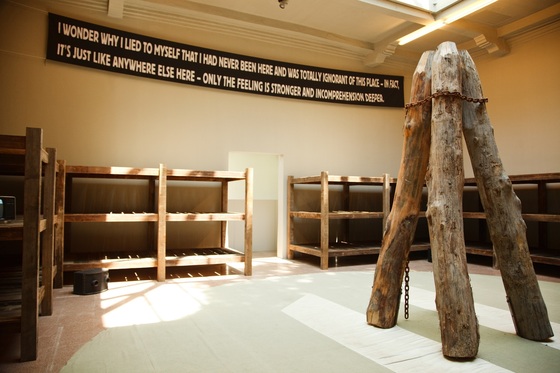

The central space is given over to an installation made especially for the biennale. A reconstruction of a gulag dormitory surrounds a Venetian gondola mooring — a tripod of rough-hewn wooden posts, chained together — with new versions, in Russian and English, of a banner from a 1978 Collective Actions performance draped across the walls. “I wonder why I lied to myself that I had never been here before,” it says. “In fact, it’s just like anywhere else here, only the feeling is stronger and incomprehension deeper.”

Mr. Groys, who coined the term Moscow Conceptualism in 1978, says that the work of the Moscow Conceptualists, while itself nonideological, was “about the society defined by ideology.”

“In the Soviet Union we had dissidents and protests, but there was a lack of understanding, of analysis,” he said. “Moscow Conceptualism wasn’t about protest, it was analysis.”

For Ms. Kesaeva, “Conceptualism is not political — it’s thinking about the philosophy of art, deeply.”

“It’s about life and mystery,” she added. Mr. Monastyrski, she said, “is a philosopher and a historian.”

In a typical Collective Actions performance, participants would be summoned by telephone or word of mouth, much like a modern-day rave party, to a field or a forest clearing outside Moscow where, often in the biting mid-winter cold, they would wait, shivering, for something to happen. The happening itself, surreal, sometimes pranksterish, often on the periphery of vision, might last only a few minutes; then the participants would go home again, to record and debate what they had seen or heard: A man with a balloon-head that he burst before himself disappearing? A singing kettle buried steamily in the snow? A bark without a dog?

The open space, and the intangible event — what Mr. Monastyrski called an “empty action” — were designed to create an “empty zone” where structured perception was obliterated, opening a momentary space for individual dreams. In a centrally commanded, “progressive,” utilitarian Soviet society it was a gesture of subversive silliness. Monty Python in a prison camp.

After perestroika, the loosening of state control by President Mikhail Gorbachev in the 1980s, Moscow conceptualism won recognition among many contemporary critics and historians as “the most important art movement since World War II,” Mr. Groys said, in part because it instigated the explosion of performance art in Russia.

Yet for a broader public, both inside and outside the Soviet Union, it remained largely inaccessible. Some of those who worked with Mr. Monastyrski in Collective Actions — an ever-changing group that has seldom numbered more than 30 participants — have gone on to fame abroad. (Ilya Kabokov and Erik Bulatov were among his collaborators.) But Mr. Monastyrski himself has remained an insider’s secret.

One reason for his inaccessibility, Ms. Kesaeva and Mr. Groys said, is that like many Soviet artists, he was fundamental disconnected from the market economy — the touchstone for contemporary artistic success. Even now, in his 60s, working often in video, and downloading to YouTube, he remains blithely uncommercial.

In the West, art has long been defined by its market, but in Soviet Russia “there was no art market,” Mr. Groys said. “Artwork was defined by its ideological value. The Soviet Union was not a money-driven economy. It was a symbolic economy.”

Mr. Monastyrski made his living as a book illustrator and stage-set painter. He “and his group never lived from their art and never wanted to get money,” Mr. Groys said. “As Marcel Duchamp said, the way to keep your independence as an artist is never to make a living with your art.”

In an art world awash with billionaire collectors searching for the next big thing, Mr. Monastyrski’s anti-commercialism makes him an oddity. Showing him in Venice, Ms. Kesaeva said, “is not about business.”

“This is about something else, something far more important,” she added.

From the wife of a billionaire oligarch (Igor Kesaev, who made his fortune in tobacco), this can be considered a statement of defiance. Ms. Kesaeva came quite recently to the Russian contemporary art scene, establishing her Stella Foundation in 2004. And though she has built a solid track record as an organizer of successful international shows, her appointment to run the pavilion in Venice for the next three years raised hackles in the Moscow cultural world where oligarch wives and girlfriends get a wary reaction.

Leonid Bazhanov, a curator of the pavilion in the 1990s, who is now director of the National Center for Contemporary Art in Moscow, was among the doubters. It was “a bit of a strange decision,” Mr. Bazhanev said this year, speaking of Ms. Kesaeva’s appointment by the Russia culture minister, Alexander Avdeev. “Nobody knows how it was made. When I was appointed, there was a selection process, a competition. Now there isn’t.”

Another assessment was offered by Alexander Yakut, an artist and founder in 1989 of the first private contemporary art gallery in Moscow.

“Stella Kesaeva has got some influence in the Russian contemporary art circles,” Mr. Yakut said in an e-mail. “The appointment of her to this post is with no doubt a question of money.”

Still, the oligarch’s wife and her resolutely uncommercial protégé added a quixotic counterpoint the this year’s biennale, and a rare sense of mission.

“The dogs bark,” Ms. Kesaeva remarked of her detractors: “The caravan moves on.”