Stella Kesaeva: Collecting as a Mission

Sophia Kishkovsky, Russian Art Focus / 02 August 2021

The Russian art patron, who showcased Moscow Conceptualist art to the world when she was at the helm of the Russian national pavilion at Venice biennale, is undaunted by the COVID-19 lockdowns.

Stella Kesaeva is a commanding and forward-looking presence on the Russian contemporary art scene, who made an international mark as Russian pavilion commissioner at the Venice Biennale in 2011–2015.

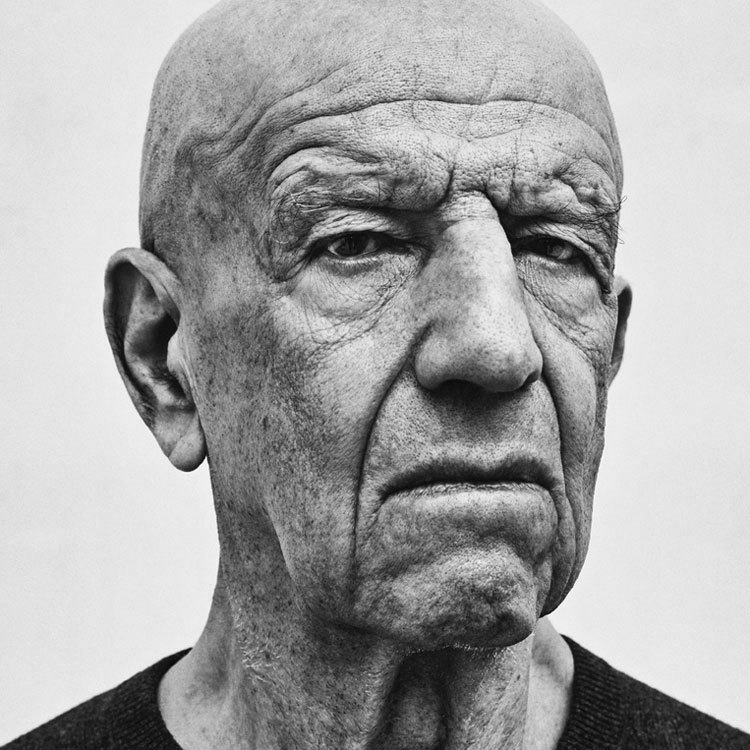

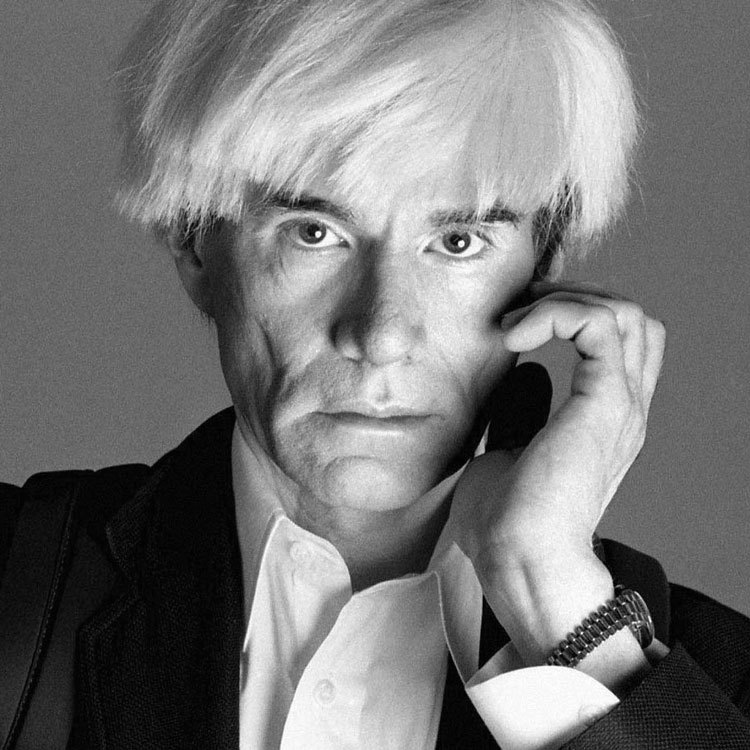

Unlike most Russian art collectors who came into wealth in the post-Soviet era, Kesaeva never went through a phase of collecting 19th century Russian paintings. There are no forest scenes by Ivan Shishkin (1832–1898) or seascapes by Ivan Aivazovsky (1817–1900) on her home or gallery walls. Her first purchase was Andy Warhol’s (1928–1987) acrylic and silkscreen ink on canvas ‘Cat’ (1975), in preparation for the first exhibition in 2003 at her Stella Art Foundation, ‘American Figures. Between Pop Art’ and Trans-Avantgarde of work by Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960–1988) and Tom Wesselmann (1931–2004).

Before launching her pioneering artspace, Kesaeva had lived with her family for a long time in Geneva, a base for visiting “practically all of the major museums and galleries in Europe”, which left a lasting impression.

“Especially everything connected to contemporary art,” she says. “Frankly speaking, I love everything modern and innovative much more than historic and antique. That is why I devoted particular attention to contemporary art. So I never thought of buying classical Russian art for my collection.”

Kesaeva is a champion of Moscow Conceptualist artists, who bypassed Soviet reality into another dimension. She vividly recalls her first impressions of Ilya and Emilia Kabakov’s (b. 1933 and 1945) ‘Palace of Projects’ exhibition and his installation for the ‘New Angelarium’ exhibition (MMOMA, 2007), the wings of an angel strapped together with leather, accompanied by a drawing of a man with wings sitting by a table writing.

“This drawing reflects Kabakov’s attitude to wretched Soviet reality,” says Kesaeva. “The artist is contemplating the whereabouts of body and soul. This work amazed me, because I remembered that in childhood my table stood by the window in exactly the same way and I spent quite a lot of time there doing homework. I constantly looked out the window and it seemed that I could, like a bird, fly out of the room and to far off wonderful lands. Just like the protagonists of Kabakov’s works, I wanted to flee into another dimension. This work is very dear to me, one can say that it was then that contemporary art and I started speaking the same language.”

The Stella Art Foundation worked with the Guggenheim Museum and the State Hermitage Museum to bring the Kabakovs’ ‘An Incident in the Museum and Other Installations’ to St. Petersburg in 2004, also the artists’ first visit to Russia since their emigration, which was “very emotional”, according to Kesaeva.

She speaks in similarly transformative terms of experiencing and acquiring works by Bill Viola. She was struck by his video installation for a production of Richard Wagner’s ‘Tristan und Isolde’ at the Opéra Bastille in 2005, conducted by Valery Gergiev, decided it must be shown in Russia and, several years later, ended up visiting the artist’s studio where she bought part of it, ‘Isolde’s Ascension’: “I’d never seen anything like it: not an artist’s studio, but an entire film studio where he poured out this water, tons of water, with a huge amount of equipment, actors and actresses.”

Of 1,500 works in her collection, managed by the foundation, an eclectic range of 50 from Spencer Tunick (b.1967), Robert Mapplethorpe (1946–1989) and David Salle (b. 1952) to Moscow Conceptualist leader Andrei Monastyrski (b.1949) and Ukrainian contemporary art pioneer Alexander Gnilitsky (1961–2009), hang in her Moscow home. Salle’s painting, in her living room, was purchased for a 2004 exhibition by the foundation. Kesaeva is drawn by Salle’s philosophical, stylistic and visual juxtapositions and says she loves the painting “and never tires of it”. Most of her collection, she says, was purchased directly from artists or dealers, rather than at auction, and she has never regarded it as a financial investment. “I don’t really like to participate in auctions for various reasons,” she said. “It has always been easier for me to agree on a price and purchase a work.”

Kesaeva’s Venice role was an investment in promoting Russian art abroad. Stella spent millions euro of her personal funds to provide the success of the Biennale projects. She made a strategic decision to focus on Moscow Conceptualist art to bring something new to the world. At each biennale, the pavilion was turned over to one artist: Monastyrski and his ‘Collective Actions’ group; Vadim Zakharov (b. 1959) (his ‘Danae’ installation rained gold coins on female spectators) and Irina Nakhova (b. 1955). The respective curators Boris Groys, Udo Kittelman and Margarita Tupitsyn also played a central role.

“I think that the main characteristic of Russian art of the post-Soviet period has been its isolation from the outside world,” she says. “Its alienation,” a carryover “from the times of the Iron Curtain and the totalitarian policies of the USSR.” As a result, Russian art was virtually unknown in the West; artists in Russia and even those who emigrated from the USSR “are not part of the global artistic community”, affecting the quality of their work, which includes “a great deal of works derivative of what was created in the West much earlier”.

“Conceptualism, on the contrary, it seems to me, is one of the original trends in Russian art,” says Kesaeva.

The Stella Art Foundation, she said, has big plans with “a number of European museums and foundations”, on hold for now, due to Covid-19. It will continue working with the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts (at Venice, in 2019, they co-presented ‘There is a Beginning in the End. The Secret Tintoretto Fraternity’).

Kesaeva says that although pandemic lockdown put the brakes on her foundation’s projects last year, work has resumed. She was not derailed as a collector, because “I cannot call collecting my passion”.

“Of course, I watched films like ‘The Thomas Crown Affair’ and I remember a sensational story about a Japanese collector who threatened to bury himself with a Picasso painting. But, in my case, collecting is more of a mission, the meaning of life. I try to approach collecting in moderation, with a calculated mind.”