Breugel, Conceptualists Side by Side in Vienna

Max Seddon, The Moscow Times / 22 May 2009

For any artist, the honor of an exhibition in one of Europe’s major museums is a rare one indeed. The chance to show one’s works alongside Renaissance masterpieces that are printed in every art history textbook is rarer still. “In Situ,” the Igor Makarevich and Elena Elagina exhibition organized by the Stella Art Foundation, which flew over a group of journalists for the show at Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum, is just that. Here, for the first time, Russian contemporary art stands side by side with works by the likes of DЯrer, Rubens and Van Dyck — and looks no worse for the comparison.

Makarevich and Elagina, a married couple working together since 1990, were at the center of the Moscow Conceptualist School that dominated unofficial Soviet art. Quite literally, in fact. With no legal way to discuss, exhibit or sell their works and no money even for the most basic materials, artists met in his and Ilya Kabakov’s apartments, transforming them into vibrant pockets of underground activity. But while Kabakov and his wife Emilia have long enjoyed international recognition, fame for the “other” Conceptualist couple has been far slower in coming.

“In Situ” should change all that immediately. Curator Boris Manner has not only put them into direct contact with the Kunsthistorisches Museum’s collection but has also integrated them seamlessly into the Western artistic canon that it displays. The room with 10 works by Flemish “peasant painter” Pieter Breugel the Elder, considered the museum’s piece de resistance by many, now has a new centerpiece: Makarevich and Elagina’s “Mushroom Tower,” which places a replica of Vladimir Tatlin’s never-built “Monument to the Third International” atop large psychedelic fungi.

One Breugel painting in particular was key to Makarevich’s artistic development and served as a measuring stick against which he created and judged his own work. “When I was young, I came across a reproduction of Breugel’s ’Tower of Babel’ in a textbook,” Makarevich said. “It set me a riddle. All my life, I tried to solve this riddle, and I felt I never did. You could call a large number of the works here attempts to answer it.”

Much as Breugel did by transposing the scene from ancient Babylon to medieval Flanders, Makarevich and Elagina have readapted the Biblical theme for their own times. Mushrooms are a key motif in their interpretations of historical memory and his attitude to the heady utopian dreams of the Soviet Union. Here they imply that the wild hope for the future that the Russian avant-garde drew from the 1917 Revolution, represented here by Tatlin, was ultimately nothing more than a hallucination, a building project as unreasonably ambitious and doomed to failure as Breugel’s crumbling tower.

“What,” Makarevich added, “is the Great Utopia if not an attempt to reproduce the Tower of Babel? Our work constantly interprets some or other part of our lives, our consciousness. We were bricks in that tower.”

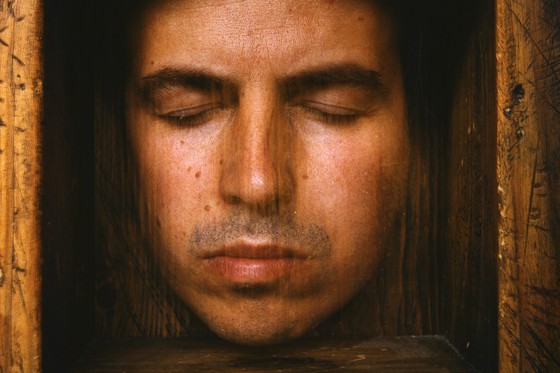

Most of the other works join the Renaissance paintings in dialogue through Manner’s curatorial juxtaposition. The “Closed Fish Exhibition,” an idiosyncratic reconstruction of a lost 1935 exhibition in Astrakhan, is scattered alongside two fish market paintings by Frans Snyders, almost implying that even those Dutch masters could themselves have been remade by the Russians. Makarevich’s “Homo Lignum” project, about an alienated Soviet factory worker who tries to turn himself into a tree, and Elagina’s musings on the Soviet pseudo-scientist Olga Lepeshinskaya, however, are presented on their own as works from the museum’s collection — as if simply to assert that they belong here.

And the answer is an unquestionable yes. This exhibition is an entirely deserved accolade, a triumph and a breakthrough — not just for them but Russian art as a whole. Hopefully, it will not be the last of its kind.